Young People Aren't Avoiding News. They're Avoiding You.

New research from FT Strategies and Knight Lab breaks the myth — plus why the "E" in STEPP matters more than ever, and what we're up to at the Saudi Media Forum.

How a 50-year-old newsroom experimented with social media creators to reach communities it hadn’t reached before while keeping loyal readers engaged

For many newsrooms, sustainability comes down to one thing: finding new readers who will stick around and support the work. The problem? Many are still relying on methods that worked years ago. High Country News (HCN) was one of them. Founded in 1970, the independent, reader-supported newsroom built its reporting in “the spaces in between”— serving politically mixed rural communities across the West shaped by water, land, Indigenous sovereignty and climate.

For 50 years, direct mail was how most people discovered High Country News and became subscribers. But, over time, this system became expensive and ineffective. In 2023, HCN turned to social creators to introduce their journalism to new communities and future supporters. Did it work? The story is still in progress, but the shift is clear. What started as an experiment with one creator has grown into an influential roster helping HCN show up in conversations it could not reach on its own.

When Gary Love joined HCN in 2020 as Director of Product and Marketing, the newsroom reader acquisition strategy relied almost entirely on direct mail. To make the costs worthwhile, they had to target the same types of readers again and again, limiting growth. With weak data to guide decisions, the newsroom spent more each year just to replace subscribers who left.

“It was an angry cycle we needed to break,” Love told Influencer Journalism.

Audience segmentation wasn’t the only issue. Polarization was also impacting the business.

High Country News had long served areas that, as Love puts it, were “a whole lot of purple.” Readers with libertarian views, skeptics of power and often ignored by national media. That began to change during the first Trump presidency, when coverage that once spoke to a broad mix of readers started to cause stronger reactions, and tolerance for nuance was shrinking.

“Any mention of Trump triggered what I call rage quits, people who didn’t just leave but wanted you to know exactly why,” Love said. “At the same time, we saw an influx of donations and new subscribers from outside ‘the spaces in between’. It marked a huge shift in our audience.”

Then came the pandemic, another layer that reshaped how the newsroom worked.

“We had and still have an office in Paonia, Colorado. That’s our home,” Love said. “But the pandemic was the moment when the company released the idea that everybody needed to be based there. We became a mostly remote company, with just a small portion of folks working directly out of the office.”

That shift expanded the range of stories the newsroom could report across the West. But it also complicated audience focus.

“Traditionally, the stories you cover are the ones you see when you walk out of the office,” Love said. “You can see the coverage in front of you. You can see the readership in front of you. When you’re working remote, it can be difficult to keep that focus on the audience and that necessary coverage when you’re more spread out across the West.”

The challenge was clear: how do you reach new audiences without alienating the base that had sustained the organization for decades?

High Country News needed to innovate. That’s when they moved part of their direct mail budget into paid collaborations with social media creators, people who already had trust, reach, and fluency on platforms HCN didn’t. The other half of the budget went into improving HCN’s technology and data quality, especially around conversion rates.

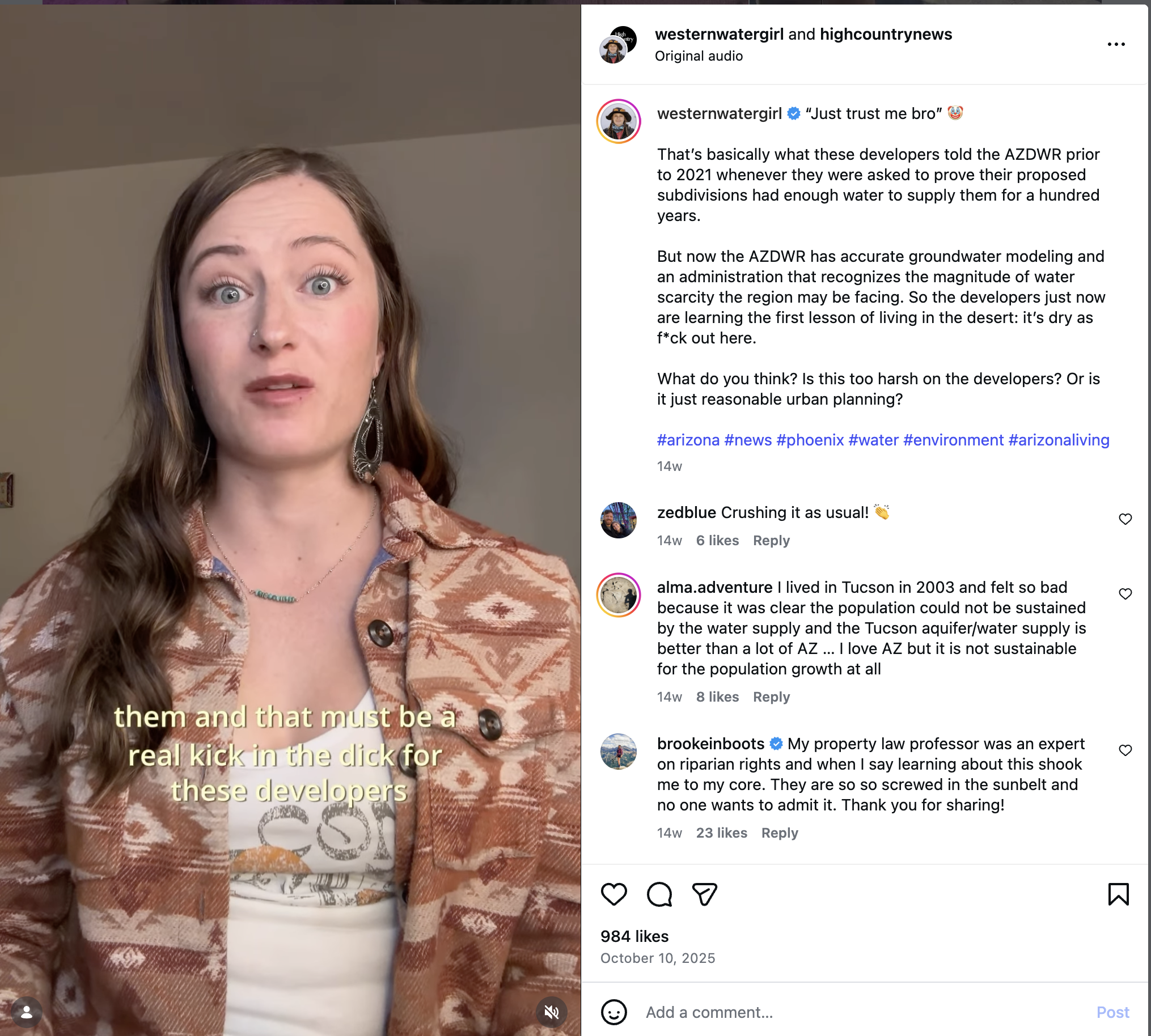

One of those creators was Teal Lehto, known online as @westernwatergirl, who explains Western water policy to nearly 100,000 followers across TikTok and Instagram. After she shared an organic video about HCN’s coverage, the newsroom reached out with a proposal for a long-term partnership, which they announced in a cross-posted video in June 2023.

“We realized that we would need to find other individuals and groups who have their own network — to be partners,” Love told Influencer Journalism. This wasn’t a new idea for HCN. The newsroom had done something similar with teachers through the HCNU Classroom Program, building relationships with educators who could help extend its reach. The goal wasn’t immediate conversion, but exposure through people audiences already trusted. To find their “ambassadors” online, Love and his team would ask themselves: “Does someone trust this person for a particular topic that’s important to High Country News?”

When it comes to metrics of success, Love watches for signs of resonance: people commenting, naming High Country News, and engaging deeply with the topic. “That’s when we feel really happy, when people are becoming familiar with High Country News in those conversations.”

Lehto’s videos don’t look or sound like traditional journalism, and that’s the point. Her content blends humor and astrology memes, urgency, outrage, and blunt language (even curse words) to explain complex policy issues in a way that feels native to TikTok and Instagram.

While she often emphasizes solution-driven content and good news, the style sometimes functions as rage bait, sparking strong emotional reactions that drive comments, shares, and debate. She also uses green-screen effects, question boxes, and captions to create community-driven content, respond to news, combat misinformation, and amplify High Country News’ reporting.

“I usually take two to five hours to research, another one to two hours to write the script,” Lehto told Influencer Journalism. “Recording takes about an hour, editing another two or three. In total, it’s about 10 to 15 hours of work for a single video.”

Her process is intentional. She starts by identifying the emotional root of a story—what people are confused about, angry about, or afraid of—and then works backward. She builds scripts around the questions most people would ask, layering in background, tradeoffs, and why the issue matters now. It’s an approach that mirrors what Influencer Journalism founder Adriana Lacy describes in the STEPP framework: social currency, triggers, emotion, public visibility, and practical value. Lehto learned that language by living on the platform.

“You need to be on TikTok, scrolling daily, to understand the culture,” she said. “Most nonprofit newsrooms don’t have the time or staff for that.”

HCN checks scripts for factual accuracy, but they don’t dictate tone, format, or delivery. They also don’t republish her videos to their own subscribers.

“Teal isn’t for our audience,” Love said. “Teal is for exposing High Country News to her audience. She is the expert on her audience, and we rely on that. We don't want to do anything that would stop that from happening just because it’s what we need.”

Lehto agrees: “They really respect the voice that I bring to the table. As long as it’s factually accurate, they let me use my own voice.”

Love reinforces the unique value of Lehto’s ability to find the emotional core of policy stories, something that helps people connect before they ever see a brand name.

High Country News also explored affiliate links with creators, but some of these partnerships simply didn’t feel authentic and failed. They also encouraged some reporters to create videos for HCN’s social channels, but many struggled to navigate the culture and language of platforms like TikTok. “Not every reporter has the skill set to do this well,” Love said.

Inside HCN, Love and Lehto said the partnership didn’t find any resistance. Love attributes that largely to the fact that the videos live on Lehto’s own channels and do not run through HCN’s socials, website or newsletters.

But the relationship between other journalists and the creator is not free of tension.

“Some reporters at a big conference have said ‘This woman is coming for my job,’” recalls Lehto. Others argued she didn’t belong at the same table. Lehto always clarifies that she is not a journalist — she doesn’t conduct interviews or do the ground reporting.

Journalists’ responses to her work are mixed: some are grateful for the visibility she gives, while others request tags or raise concerns about credit. “There was an author who reached out to me and was like, ‘you’re not adequately crediting me’ and I explained to them: ‘look, I had the date of publication, the publisher, your name and the article. That’s all the stuff that would be required in an APA citation, but there is no official format to cite sources online.’”

She always includes the reporter’s name and publication in the caption and video, but notes the need for a clear, standardized way to credit stories online. “I hope that in the future there will be some kind of conversation about the correct way to cite things in digital spaces.”

What did work was reaching highly influential audiences. Many federal workers, policymakers, and people actively engaged in legislation follow Lehto, some anonymously, given political sensitivities. A campaign sharing free HCN subscriptions for federal workers performed particularly well, reaching the exact community HCN wanted to engage while staying true to Lehto’s voice and maintaining trust with her audience.

Over time, the impact became visible, even without traditional metrics.

“People started associating ‘Western Watergirl’ with High Country News,” Lehto said. “People would come up to me at conferences and say, ‘What you’re doing with High Country News is so cool.’”

Some stories traveled especially far. One video that highlights a joint report by ProPublica and High Country News about a hospital on the Navajo Nation that couldn’t open because it didn’t have access to water infrastructure went viral on both TikTok and Instagram. Shortly after, the hospital opened. When honored by Hydro20 for her innovative use of social media to educate millions about water policy, Lehto described this as one of the most rewarding moments of her work—her coverage, alongside the investigative reporting and other factors, helped apply public pressure that made a real difference.

“It became valuable enough that they didn’t need metrics to prove it,” Lehto said.

The partnership also created tangible benefits for Lehto. Working with a legacy newsroom brought legitimacy, consistent pay, and speaking opportunities.

For High Country News, success looked less like immediate subscription growth and more like presence: being part of conversations they couldn’t reach on their own.

That success led HCN to expand its creator partnerships across platforms. Some connections came through Lehto, others via direct outreach—a process Love describes as challenging and time-intensive. To help scale these efforts and better measure impact, the newsroom is exploring tools like Verified Storytellers, a creator-matching service powered by Influencer Journalism.

“And we’ve got a couple more that we’ve made the connection with, are building the relationship, and we’re just looking for the right story. So, a few more to come,” added Love.